Hope is a thing with feathers

On theatre as a medium for social criticism & the usage of masks and bird symbolism in "A Treachery of Swans"

A.B. Poranek's fantasy YA novel A Treachery of Swans is based on the ballet Swan Lake and takes us to a 17th century France. We follow 17-year-old Odile who has been tasked by her father, a vengeful sorcerer, to restore magic to their kingdom. To succeed in this quest, she must assume the identity of the noblewoman Marie d'Odette, a childhood friend turned enemy, in order to infiltrate the castle and steal the crown in which the magic is restored.

The novel is pitched as “a sapphic retelling of the Swan Lake,” which is what tweaked my interest from the beginning, and was one of the main themes I was expecting in the novel. Thus, at first I was skeptical as I felt the sapphic aspect to be just that, an aspect, rather than the pillar the story leaned on. I didn't have a problem with the way the relationship itself was described or its character, in fact I always liked the relationship between Odile and Marie. Perhaps my expectations were too high and therefore I couldn't shake the feeling of disappointment when the relationship remained in the shadows, so to speak. But towards the end (maybe 60% into the book) their relationship and love for each other became more prominent, and I really enjoyed finding out about their (shared) past.

Something else that bothered me was the ending. It felt a bit rushed considering Odile's main goal was to restore magic to the kingdom. Also, the epilogue left me a little conflicted. I think the story could have ended without it, and thus kept the door open for a possible sequel. (Yes, in theory there could be a sequel but the fate of Marie and Odile would remain a question that drives the reader on).

Symbolism, vol. 1: Theatre

The novel opens with the night before the Dauphin's 18th birthday, the day he is to choose his future wife, at the Théâtre du Roi where Odile works as an actress. The theatre theme/symbolism follows us throughout the novel as its structure is made up of scenes rather than chapters, the characters in the book often wear masks (both literally and metaphorically), and the way the noblesse acts are compared to the theatre, e.g. they have powdered faces and wear perukes and ostrich feathers.

Discussing, portraying or criticising social issues through theatre is not a new practice. In Jude D. Russo’s article “The Meaning Behind the Mask: Social Activism Through Theater”, Russo points out how social commentary on the Roman stage was limited to certain genres, which in the Middle Ages gave way to aggressive social commentary.1 Another thing Russo emphasises in the article is the different ways in which theatre can be used to comment on societal problems, e.g. allowing theatre as an art form to be strong enough on its own to make these comments, i.e. not “forcing” the message.2 Moreover, as a medium, theatre is highly communicative and largely based on the communication between the actor and the audience. It is the actor who embodies the problems on stage, allowing a detachment from the playwright. Their opinions are hidden in the plays, partly because not all the characters have the same point of view, and partly because it is the actors who are on stage, whereas the playwright is not present in the production. In other words, theatre is an excellent means of expressing social criticism, and there are many examples of plays reflecting political, moral and ethical issues that have been (and still are) at the forefront of society, e.g. racism and patriarchy is criticised in Lorraine Hansberry's play A Raisin in the Sun; war in Lynn Nottage's play Ruined;3 the effect of the Israeli occupation is depicted, among other things, in the anthology Inside/Outside: Six Plays from Palestine and the Diaspora;4 and fascism, antisemitism and sexual norms are criticised in the musical Cabaret.

Returning to the use and symbolism of masks, masks have been used in theatre since its beginning. In ancient Greece, for example, masks were used to separate the different characters portrayed by three actors, while at the same time making the actors visible to the audience in the large amphitheatres.5 Similarly, masks were used as a means to portray the archetypal characters of the Italian theatre commedia dell'arte during the Renaissance,6 and in the ancient Japanese theatre form Noh, the masks were considered to “possess a certain inherent power, transcending them from mere props to profound symbols of transformation.”7 David Roy also emphasises the religious/spiritual nature of masks in the article “Masks and cultural contexts drama education and Anthropology”, naming the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (which after Christianisation became better known as Halloween) which had a tradition of wearing masks to hide from evil spirits, as did Christians on All Saints Day in the 15th century to avoid being discovered by the spirits of the dead.8

Given this, I find it interesting that the characters in Poranek's novel wear actual masks and that the nobility are said to be dressed up. May this be an attempt to free the wearer from societal pressure, for disguised behind a mask they have the freedom to choose who they want to be, how they represent themself? Roy (2015) writes about the Venetian Carnivals and the usage of masks: “By freeing the wearer to be ‘other’ than they were, a separation between public and private life without judgment in the close city conditions was allowed. […] The citizen found that by wearing a mask, they could act like a stranger.”9 Similarly Odile describes how donning a mask is like stepping away from her own dull skin. On the other hand, masks are also worn by the Château staff, a tradition that the previous king mandated. The masks worn by the staff is described to offer limited peripheral vision, certainly mandated to keep the secrets of the king and the court and as a means of power play, for once you go up in the ranks you don’t have to wear a mask. Lastly, I also thought about the term persona and its etymology and psychological meaning. We all wear masks to fit into the normative society, and thus, the masks could also offer a message: the people with whom we can take off our masks are people we should hold tightly to, for it is in their presence that we can fully bloom. Whatever role the mask and theatre are supposed to play in the novel, it is incredibly interesting and rewarding to analyse.

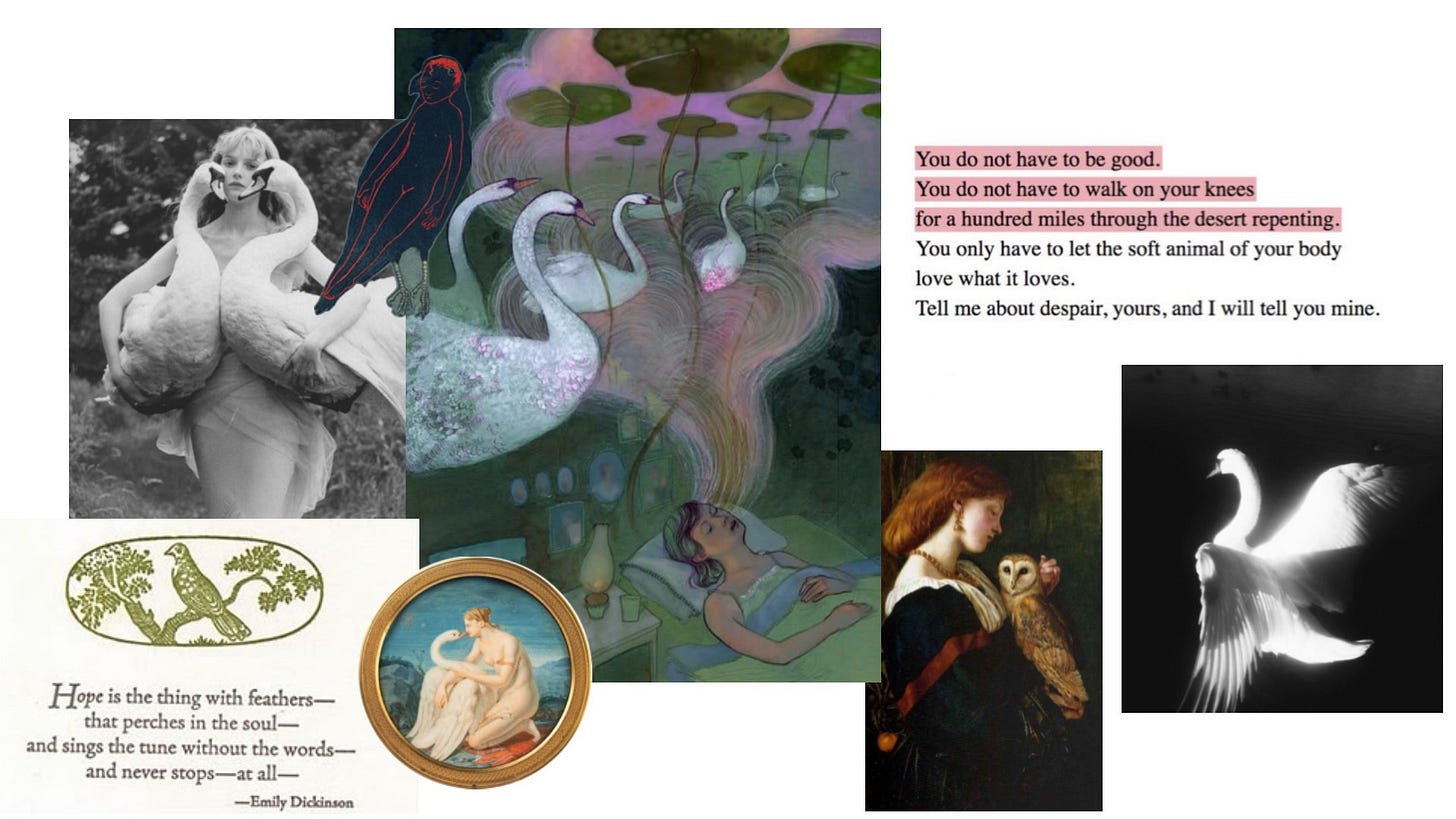

Symbolism, vol. 2: Birds

Birds are already present in the title of the novel and in the fact that the novel is based on Swan Lake. In addition, “being trapped in cages as birds” is used as a metaphor for the societal pressure faced by the characters (see Maya Angelou's poem “Caged Bird”10 and her autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings), the castle has tapestries with caged birds on them and the characters are associated with a bird of their own: a crow, a swan and an owl – more about this later.

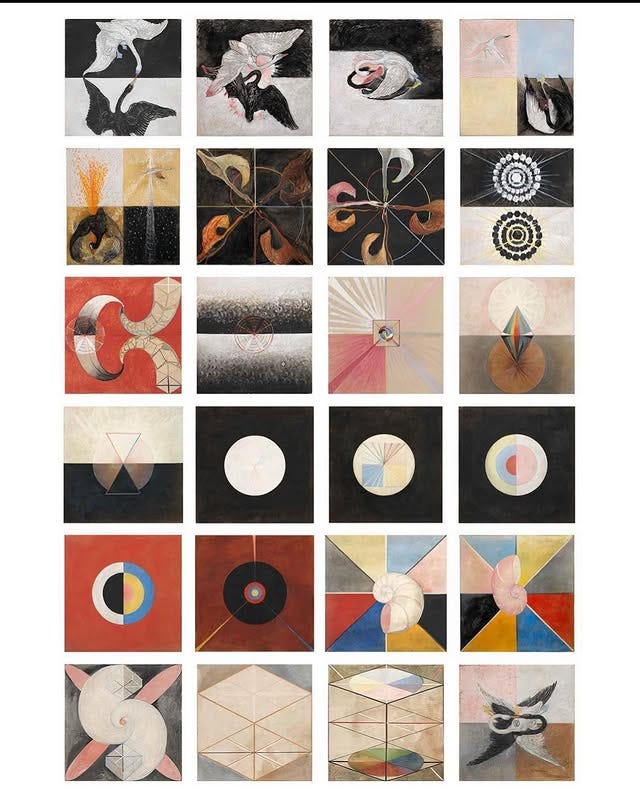

Birds have been prominent in art and folklore throughout history, e.g. in greek mythology we find stories featuring crows (Apollo who turned a crow lying to him into a constellation), owls (Athena's companion) and swans (Leda meeting a swan who turned out to be Zeus in disguised).11 Moreover, birds have been present in literature and other forms of art and pop culture through history, e.g. owls are mentioned in Arthurian legends, Macbeth, Julius Caesar and Parlement of Fowles,12 and motifs of the swan can be found, on the cover of Mazzy Star's album “Among My Swan” (1996), Björk wearing a swan maiden dress in 2001, and in Swedish artist Hilma af Klint's swan series (photo below from Instagram):

It is clear that the birds with which the father, Marie and Odile are associated are carefully chosen because traits and myths commonly associated with each bird are also found in the characters. In fact, Poranek’s debut novel Where the Dark Stands Still (2024) is heavy on mythology and in a post for United by Pop Poranek writes that the novel draws on three primary elements: Slavic mythology, Eastern European folktales, and Polish culture.13 In A Treachery of Swans certain myths and folklore can also be found, e.g. folklore surrounding the swan maiden. Marie is called “the swan princess/maiden”, and swans are often described as elegant, tranquil and angelic, as is Marie. For example, Odile often describes Marie as an angel, as the bearer of light. She is also often contrasted with Odile, who describes herself as darkness. Together, Marie and Odile are thus the white and black swans that so often appear in art (see for example the film Black Swan or Hilma af Klint's painting The Swan, No. 114 from 1915). Odile, on the other hand, is called “little owl” and wears an owl pendant. In addition, she is trained to be sorceress, and owls are actually associated with witchcraft and magic, e.g. an owl wing is used in the magic potion in Macbeth, the goddess of the underworld Hecate was believed to have an owl as a companion, just like Merlin in the Arthurian legends.15 Lastly, the father wears a bird mask and is often compared to crows. Crows are birds that are rarely portrayed in a favourable light and are often described as adaptable, smart, cunning and bold – traits that the father possesses.

Overall, I would recommend this book. The world building and the fact that magic/sorcery is described in such detail leads to a sense of intimacy because you know how everything is structured and how it affects the characters. Also, the stakes are really high right from the first page, the plot twists are ones you don't see coming and the changes made to the original Swan Lake story are genius! Cannot wait to see what Poranek publishes next.

This is a more in-depth version of the review I originally posted on my StoryGraph (found here). .☘︎ ݁˖ ARC received in exchange for an honest review. Thank you Edelweiss!

Jude D. Russo, “The Meaning Behind the Mask: Social Activism Through Theater”, The Harvard Crimson, April 8, 2015, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2015/4/8/arts-cover-activist-theatre/.

Russo 2015.

Ruined depicts women’s life during the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (check trigger warnings!).

Further reading: Une Saison au Congo (eng. A Season in Congo) depicts the last months of Patrice Lumumba’s (the first president of the Republic of the Congo) life during the transition to independence of the Belgian Congo & the anthology Contemporary Congolese theatre features three plays by authors from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Further reading: Sykes-Picot: The Legacy (Five Modern Plays by Hannah Khalil, Hassan Abdulrazzak, and Joshua Hinds) (2015) edited by Kenneth Pickering, Palestinians and Israelis in the Theatre (1995) edited by Dan Urian, Palestinian Theatre (2005) by Reuven Snir & Double Exposure: Plays of the Jewish and Palestinian Diasporas (2016) edited by Stephen Orlov & Samah Sabawi (Source: Marjan Moosavi, https://www.critical-stages.org/15/insideoutside-six-plays-from-palestine-and-the-diaspora/).

David Roy, “Masks and cultural contexts drama education and Anthropology”, International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 7, no. 10 (2015): 215, https://academicjournals.org/journal/IJSA/article-full-text/144926455266.

Whitney Hale, “Unveiling the History of Masks in Theatre”, UKNow, October 1, 2020, https://uknow.uky.edu/arts-culture/unveiling-history-masks-theatre.

1:09–1:15 in this video: https://youtu.be/seFGdhN3Xjc.

Kelley 2008, cited in Roy, “Masks and cultural contexts drama education and Anthropology”, 215.

Roy, “Masks and cultural contexts drama education and Anthropology”, 216.

Read here for free: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48989/caged-bird.

Rachel Warren Chadd and Marianne Taylor, Birds: Myths, Lore and Legend (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

Ibid.; Peter Tate, Flights of Fancy: Birds in Myth and Legend (New York: Delacorte Press, 2007).

Make sure to check out

's post on Hilma af Klint where the painting is mentioned: https://isascorner.substack.com/p/grandeur-of-spirit.Warren and Taylor, Birds; Tate, Flights of Fancy.